Oneirogens in the witchy (Mexico) city

How the search for an elusive dream herb inspired a new way of doing dramaturgy

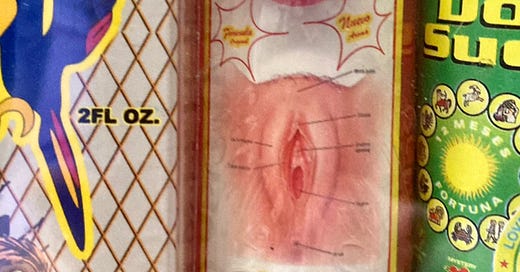

I find it a dreamlike experience in itself, navigating through the labyrinthine corridors of the sprawling Mercado de Sonora in Mexico City. This notorious section of the larger Merced market conjures the full chiaroscuro of Mexico’s magic and occult life: fortune-summoning soap bars, succulent pussy sprays, santería talismans in myriad shapes and forms, sacrificial animals both dead and alive, voodoo artefacts and ingredients, not for the faint of heart.

Surrounded by countless amulets designed to ward off mal de ojo (the evil eye), watchful eyes follow me everywhere, not missing an heartbeat, not missing an opportunity to make an extra peso or two on the fly. Magic is performed on the spot behind dingy curtains, though most brujxs here also maintain a more powerful shrine elsewhere where spells are cast and amarres are made for the good, the bad and the ugly. Death and the devil (along with many other trickster gods) are entities with whom one can negotiate and collaborate through concrete acts and offerings. Summoning and coaxing the spirit realm to do, redo or undo what mundane logic has proven unable to resolve.

A yearly fixture in my upbringing, el mercado de Sonora is one of the oneiric spaces that has accompanied me since early childhood, profoundly shaping my journey inquiry into 'witchcraft' and particularly those forms that have long been dismissed in most parts of Europe as mere folkloric superstition. My mother bought me here my first tarot deck and amulet, sealing my fate as a for ever apprentice bruja.

~ * ~

In 2023 I find myself once again in Mexico City, on a fateful trip that would introduce me to Mexico's vast patrimonio onírico: the manifold distinct ways in which Mexico 68 indigenous groups treat their dreams as a vital form of knowledge, acquired through specific forms of dream incubation, oftentimes induced by psychotropic plants.

This time around, I'm in Mercado de Sonora on a specific mission: I'm seeking the elusive Calea ternifolia, or Calea zacatechichi, the Hispanized term for the Nahuatl "zacatl chichic" meaning "bitter grass". This plant boasts numerous impressive medicinal properties, but primarily captivates the public imagination as an oneirogen—a dream-inducing herb that the Chontal people of Oaxaca State employ in their practice of dream divination. Smoked or consumed before sleep, the (lucid) dreams reveal to the shaman the spiritual origins of one's ailment or predicament. Healers master the art of dreaming, a gift - el don - often received through dreams and subsequently refined through initiation rites and years of practice.

Finding substantial ethnography or other scientific literature on the Chontal use of Calea proves tricky, I find. The ritual experts who use the plant concern a very specific group among the indigenous Chontal, and anthropological research into Mexico's so-called oneiric traditions and lineages is only starting to catch up. Across academic disciplines, oneiromancy has often received fleeting or marginal attention, perpetuating the persistent blind spot in Western onto-epistemologies regarding dreaming beyond the dominant naturalist scientific framework.

From a pharmalogical perspective, Calea's mildly hallucinogenic and oneirogenic effects have been attributed to, among other compounds, caleicine, a prodrug of the potent GABA-modulating eugenol, which lends herbs and spices such as basil and cloves their distinctive aroma. GABA serves as the neurotransmitter that acts as the brain's "brake pedal", as it lessens nerve cells ability to receive, create, or send chemical messages to other nerve cells. It governs the sleep cycle, and consequently also the REM phases responsible for our most vivid dreaming.

And it would be misguided—indeed, a distinctly Western impulse—to locate the 'spirit' of the plant within a single chemical compound or set of compounds, while disregarding the holistic complex of practices that form an integral part of the Chontal way of working with dreams and plants. Reducing their gods to pure chemistry or producto - or a very specific site of the body, like the pineal gland - is yet another symptom of la enfermedad blanca…

Finally, I discover a stand in Mercado Sonora selling bulk Calea—heaps of dusty, nondescript herb piled in large sacks. But how can I verify its authenticity? Am I being sold snake oil? … and as I catch myself thinking this thought, I remind myself—tip of the hat to Edward Said—that "authenticity" is a Western social construct, one that reinforces dichotomous power dynamics between the real and the fake, the original and the copy, the source and the derivative. Power isn't just about becoming the sole holder of truth/original/source, but about wielding the capacity to make distinctions between these poles and project these rigid categories onto a ‘reality’ that is infinitely complex, essentially undetermined, and in constant flux. Mercado de Sonora, where personal spiritual practices are continuously queered, syncretized, transmuted, and reassembled, subverts by its very existence any projections cast upon it as a 'repository of authentic indigenous wisdom'.

Does it truly matter how much caleicine I will eventually ingest?

(And snake Oil is obviously a wonderful boundary object, a repository of counter-narratives on the cusp of different knowledge systems, revealing the inner workings of colonial late-capitalism and its discontents. See also Blindboy’s delightful podcast on the medicinal qualities of venom, and this quite visceral home made video on how to distill oil from rattlesnake fat. I will circle back to imaginal snakes in a future post.)

I purchase a kilo of the bitter grass at this stand, and immediately sense I must await the kairotic moment when the "plant summons me", as many witchy friends in Mexico have cautioned me: '¡Pide permiso!' ('Ask for permission!') - or else you are trespassing and you will walk this foreign land as an unprotected stranger.

But how is this permiso to be accomplished—by me, a white Western person, with some roots in Mexico, yet living primarily on the European continent, far removed from the plant’s natural habitat, distant from the ritualistic context in which this oneirogen is traditionally consumed?

How can I be certain that if I ask something in my human and all-too-human language, the plant will understand my intent and answer me in a form of communication that I can comprehend as well?

How do things such as consent, let alone collaboration, function when you haven't established a common form of communication (as yet)?

What kind of transspecies pidgin—hat tip to Eduardo Kohn—might we begin to develop, and how might dreams come into play here? (More on this in my next post.)

~ * ~

These are precisely the questions that theatre maker Benno Steinegger and I grapple with when we convene in Brussels to conduct dramaturgical research for his new piece. Benno is an artist and theatre maker who unpacks a topic through rigorous, multidirectional inquiry until he reaches the furthest outer limits, only to then stage this 'via negativa' (or if you will, a glorious exposé of failures) in an installation or theatrical experience.

We spend hours in dialogue, sharing experiences with plant medicine and dreamwork, and exploring the intersection between these two realms. We also discuss the need to ask "permiso", and how this chafes against the Western impulse to simply take what appears 'for the taking'— seeing no inter-personal obstacles, upholding the vision high of unfettered consumer choice within an an un-spirited, depersonalised world. You can because you must, you must because you can.

In that sense, Benno has extensive experience under-taking "teacher plant dietas" in the heart of the Amazon. Following the instructions of the shaman, who assigns a specific teacher plant to him, he pledges to drink the plant preparation for a designated period, abstain from drinking, eating, and engaging in certain activities, and open himself to whatever the plant wishes to communicate to him. These transformative encounters with plants made him wonder: is it possible to collaborate on an art work with a plant (in concreto), or with plants (in abstracto)?

Our concerns are so resonant that I feel that this may very well be the kaironic time I was waiting for.

Next up: how Benno and I set sail into the dramaturgical deep under the auspices of Calea zacatechichi, on a journey as fascinating and rich as it was, at times, unsettling…

Bobinsana, one of the Amazonian teacher plants, also lovingly branded as la Sirenita de la jungle, also known for its capacity to open the heart, enhance (deep) memory and induce lucid dreaming.